2. Sustenance

Soon after becoming emperor, Mughal King Aurangzeb issued an order (farman) against proclaiming him as true propitiator of Islam on 9 April 1669. On that date, according to Ma’sîr-i-Ãlamgîrî, “The Emperor ordered the governors of all provinces to demolish the schools and temples of the infidels and strongly put down their teaching and religious practices” (cf. Sarkar 1928: 186). Aurangzeb’s Fatawâ-i-Ãlamgîrî truly mentions that the noblest occupation for Muslims is jihad (war against non-Muslims). This meant that military service provided the best career for a Muslim, and it was the business of the kings and commanders to declare every war a jihad. The practice of the military profession was made identical with the fulfilment of a religious duty [Fatawâ-i-Ãlamgîrî, Matba al-Kubra, Egypt, 1310 H., vol. V, pp. 346-48]. Saqi Mustaad Khan, the author of Ma’sîr-i-Ãlamgîrî writes: “His majesty, eager to establish Islam, issued orders to the governors of all the provinces (imperial farman dated April 9, 1669) to demolish the schools and temples of the infidels and put down with the utmost urgency the teaching and the public practice of the religion of these misbelievers.” Soon after “it was reported that in accord with the Emperor’s command, his officers had demolished the temple of Vishvanatha at Kashi” on 18 April 1669. This was the period when the Maratha chief Chhatrapati Shivaji took refuge for a few days in 1666 with the help of the local people in Banaras, after escaping from imprisonment in Agra. This fact is a proof of the people’s feelings against the government.

This news further irritated Aurangzeb. Jadunath Sarkar has cited several sources regarding the subsequent destruction of temples which went on all over the country, and right up to January 1705, two years before Aurangzeb died (Sarkar 1928: 186-89). By this order once again around a thousand temples including the city’s greatest temples like Vishveshvara, Krittivasa and Vindu Madhava, were razed and their sites were forever sealed from Hindu access by the construction of mosques.

The medieval temple of Vishvanatha stood near the bend of Chauk Road close to the mosque of Bibi Raziyya (r. 1236–1240), but nothing of it now survives. Bibi Raziyya’s mosque, occupying a central location in the ancient city, erected over the dismantled Vishvanatha temple, shows an act that effectively “islamicised” a site particularly holy to the Hindus. This mosque was built from previous materials, in particular pillars of an older Hindu temple, consists of two chambers connected by a three-arched opening; and four pillars in the middle of each chamber carry a set of lintels on which rest the slabs of the ceiling, devoid of any dome (Rötzer 2005: 53). At the next site, occupied by the present Aurangzeb mosque, only traces of Raja Todarmal’s temple, rebuilt around 1585 in Chunar sandstone less than 100 metres to the south of old Vishvanatha Temple, can be seen. The qibla wall rises above the plainly visible remains of the temple, which was not completely demolished ― in fact, merely crushed (cf. Figs. 8.1 and 8.2).

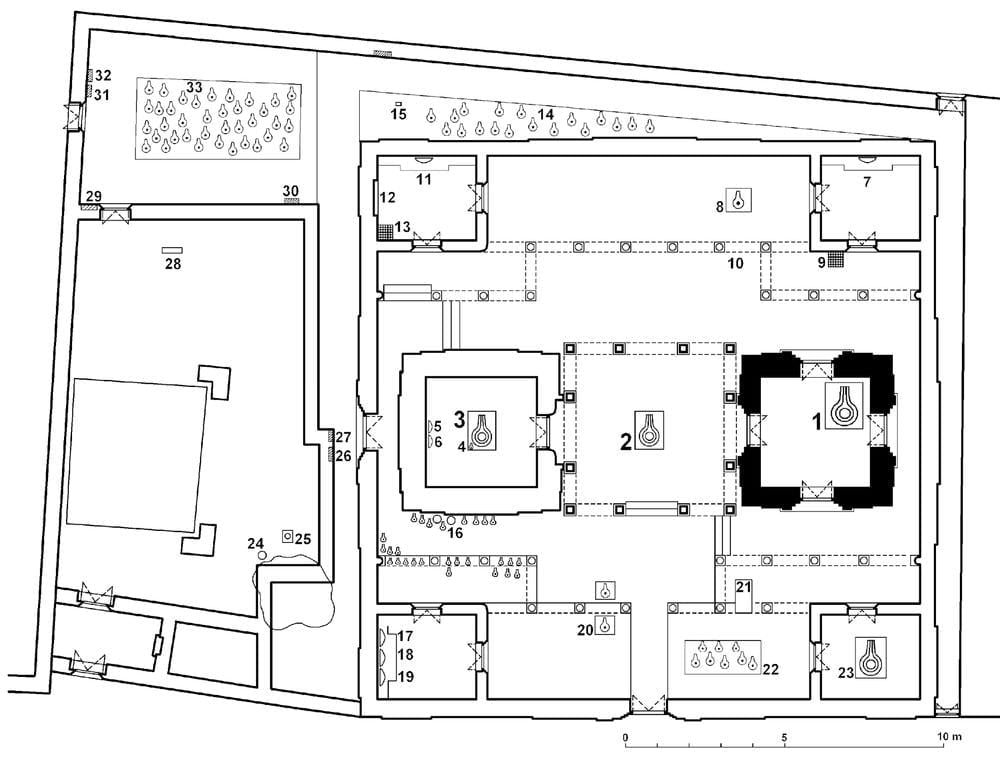

It is not easy to establish the original appearance of the temple built by Raja Todar Mal and Narayana Bhatta under the support and patronage of Raja Man Singh, a chief courtier in Akbar’s court. As for the overall plan of the monument, we have James Prinsep’s hypothetical reconstruction published in 1833, partly based on the description of the deities worshipped there as imagined in the Kashi Khanda. Prinsep’s plan visualizes the temple as a mandala (cosmogram) of 3 by 3 square chambers, the central and larger one reserved for Vishveshvara (Fig. 8.2).

The plan and architecture of Vishveshvara temple may be compared with the slightly earlier monument erected at the pilgrimage site of Brindavan on the Yamuna river by Raja Man Singh of Amber, another of Akbar’s Rajput military commanders. Dedicated to Govindadeva, the Brindavan temple of 1591 graphically demonstrates how Mughal building techniques were placed at the service of Hindu ritual requirements. Though its octagonal spired sanctuary was later demolished, a part of the temple still stands. This includes a mandapa of majestic proportions roofed with a dome raised more than 14 metres high on lofty pointed arches. Transepts leading to side porches with external colonnades give the temple an almost perfect cruciform layout. (The great Chaturbhuja Mandir at Orchha in central India erected by Bir Singh Bundela (r. 1592-1627) of Bundelkhand in the early 17th century presents a complete version of the Govindadeva scheme since its octagonal spired sanctuary is still intact). Bir Singh Bundela, a Rajput of eminence, had been a loyal supporter and friend of Emperor Jahangir from his tumultuous princely days. As Jahangir ascended the throne, Bir Singh was happily ensconced in his home state of Orchha in Bundelkhand at the north-western tip of Madhya Pradesh, and easily patronised and promoted the building of grand temples at important places (cf. Michell 2005).

We would expect to find a similar arrangement of architectural features in Raja Todar Mal’s monument in Banaras, since both this and the Govindadeva Temple at Brindavan were almost contemporary projects. (The same may have also been true of the great Bindu Madhava Temple erected at the turn of the 17th century by Raja Man Singh above Panchaganga Ghat in Banaras) (Michell 2005: 81). It is also speculated that Bir Singh Bundela was the major source behind the construction of the Vishvanatha temple, most probably around 1623 in the regime of Jahangir! Unfortunately, there is no evidence to support it.

During her reign Razia Sultana (1236-1240) had built a mosque on the deserted site of Vishvanatha temple, which had been earlier demolished by Aibak in ca 1194. By the end of the 13th century the Vishvanatha temple was re-built in the compound of Avimukteshvara and existed till the next destruction (of course partial) under the rule of the Sharqi kings of Jaunpur (1436-1458). But in 1490 Sikandar Lodi completely demolished it. Only after a gap of about ninety years, in ca 1585 with the support of Todar Mala, one of the senior courtiers of Akbar, the great scholar and writer Narayana Bhatta (1514-1595) had re-built it again, most likely on the structural plan of the previous temple of the 13th century.